Salman Rushdie does not believe in miracles, but it’s a miracle that Salman Rushdie is still alive. On August 12, 2022, Rushdie, then 75-years-old, was on stage at the Chautauqua Institution, about to give a speech, when a young man charged at him with a knife. The assailant had Rushdie at his mercy for 27 seconds. Imagine how long those 27 seconds must have felt. Some in the audience wondered if they were witnessing some strange performance art, before blood started pooling on the floor. The knife penetrated Rushdie’s legs, stomach, chest, neck, and eye: Rushdie would later learn that the blade missed his brain by “perhaps a millimeter.” One stab wound is often fatal; Rushdie was stabbed 15 times.

“You know what you’re lucky about?” a doctor would ask Rushdie during his recovery. “You’re lucky that the man who attacked you had no idea how to kill a man with a knife.”

The backstory is well-known, but still shocking. In 1988, Rushdie published his fourth novel, The Satanic Verses, which was swiftly banned in India, Pakistan, Iran, and other countries across Africa and the Middle East, for its supposedly offensive portrayal of Prophet Muhammad. Iran’s then-leader Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa in which he called “on all valiant Muslims wherever they may be in the world to kill [Rushdie] without delay, so that no one will dare insult the sacred beliefs of Muslims henceforth.” Anti-Rushdie demonstrations and book-burnings erupted the world over. Twelve people died in a massive anti-Rushdie riot in Bombay. California bookstores were firebombed for carrying The Satanic Verses; a Brooklyn newspaper was bombed for defending it. In 1991, Rushdie’s Italian translator was stabbed in Milan. Days later, his Japanese translator was stabbed to death near Tokyo. In 1993, his Norwegian publisher was shot near his home.

Rushdie withdrew from public life for a decade. It wasn’t as though he had a choice: restaurants refused to seat him; airlines wouldn’t carry him. He was aware of at least six assassination attempts over these years, all thwarted by British intelligence. Eventually, he came up for air. He moved to Manhattan and made up for lost time, weaving himself into the cultural fabric of the city. Years, then decades passed without incident. Christopher Hitchens once said that the Rushdie’s fatwa was not only a death sentence, it was a life sentence. But by August 11, 2022, the whole affair had begun to feel as though it belonged to another age.

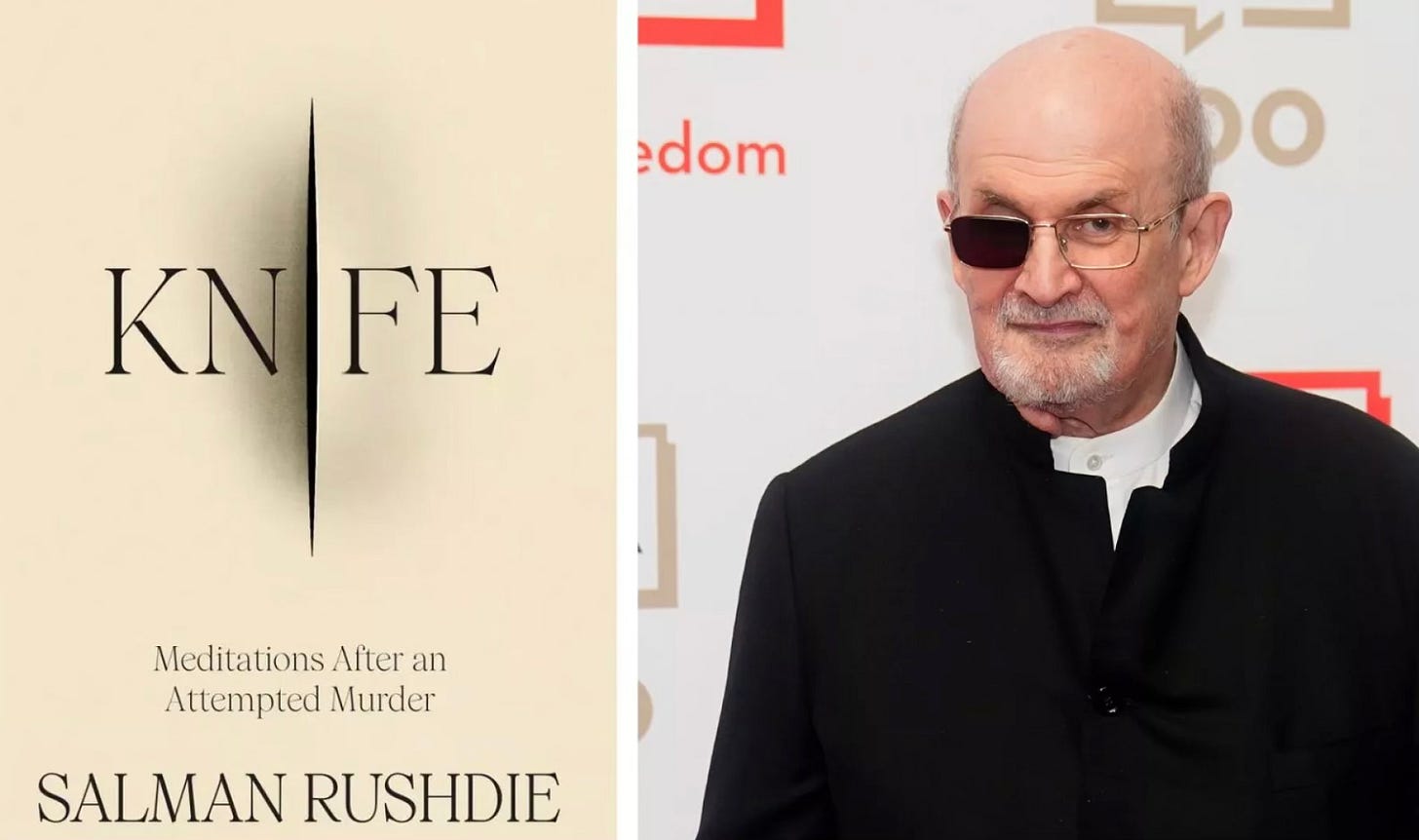

In a sense, it did. Rushdie’s would-be assassin was born years after the original fatwa was issued. He was a zealot for our time, radicalized on YouTube, trained on Twitter and Facebook. Rushdie suspects his “malleable personality found in the groupthink of radical Islam a structure for the identity it needed, and produced a self that almost became a murderer.” Rushdie calls this man “My Assailant, my would-be Assassin, the Asinine man who made Assumptions about me…I have found myself thinking of him, perhaps forgivably, as an Ass.” In Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder, he settles on calling him “the A.” One section of Knife imagines a confrontation between himself and “the A.,” which he presents in the form of a drama:

Allow me to ask: Do. You have a girlfriend?

What kind of question is that?

Ordinary question to ask an ordinary guy. Have you ever been in love?

I love God.

Yes, but human beings?...

None of your business.

I’ll take that as a no. How about a boyfriend? I heard you talk about your admiration for the real men in Lebanon. How about real men here in Jersey?

Schoolyard stuff, but understandable, as is Rushdie’s schadenfreude at the end of the book, when he stands outside his would-be killer’s jail and does a little dance. “Our lives touched for an instant and then separated,” Rushdie imagines saying to “The A.” “Mine has improved since that day, while yours has deteriorated. You made a bad gamble and lost. I was the one with the luck.”

Rushdie has always had a distinctive voice, but Knife makes us intimately aware of the authorial body behind the words. We learn more about Salman Rushdie’s material person, about his liver and intestines and bowel movements, than might have been expected. The details of his physical recovery, the hallucinations and needles and bags of “pinkish-reddish substance” drained from his lungs, are excruciating, as they must be. (“Let me offer this piece of advice to you, gentle reader: if you can avoid having your eyelid sewn shut… avoid it. It really, really hurts.”) Indeed, the authorial voice in Knife is so buoyant and chipper that one can momentarily forget that the author has suffered “life-altering injuries,” as the medical jargon goes. At one point, Rushdie closes his eyes, before silently castigating himself: “I was still thinking of my eyes in the plural then.”

Memoir, as a genre, is always torn between revelation and creation, authenticity and artifice. The author promises to reveal the truth of his experience; the narrative insists that that experience take a certain shape and conform to certain formal patterns. Rushdie presents his life immediately prior to the attack as a state of prelapsarian perfection, shimmering with love, friendship, and deeply satisfying work. Were things so perfect? Or has the narrative been massaged into shape so that Rushdie can write, dramatically: “Then, cutting that life apart, came the knife.” Or later: “The knife had severed me from my world, cut me brutally away, and placed me in this screaming bed.”

Knife is, in its own way, an ambitious book. It wants to do a lot of different things. Rushdie variously presents the book as a vehicle for understanding the mind of his attacker, and as a counter-attack against that man—an attempt to carve him up in turn. At times, he presents the book as therapeutic, a vehicle for closure. It is also a recovery narrative and a love story and a manifesto for expressive freedom. It is a bit of a mixed bag, a fascinating if also occasionally frustrating melange. Rushdie himself sounds a bit bored when he regurgitates a few pages of his longstanding quarrel with “religion.”

Knife is not Rushdie’s strongest work—but then, why would it be? Many writers like to think that they’ve suffered for their art, but Rushdie has suffered for his art. Many writers profess the need for “safe space” in which to operate, but the world has not been a safe space for Salman Rushdie. Loathed, hated, threatened, vilified, stabbed—he carries on. Physically diminished, one-eyed, traumatized—he won’t stop. Behind the words there is a body, and behind the body there is a toughness, a refusal to submit. Few of us will be called upon to pay a steeper price to live by our ideals.